Section 4 Collaborative Coding and Workflow Best Practices

Some sections of this document borrow liberally from the additional resources listed at the end of the document.

4.1 ROSSyndicate style guide

ROSSyndicate aims to incorporate the {tidyverse} style guide for our codebase. Be sure to standardize file/variable/function style and naming conventions at the beginning of the project. While this is a somewhat aspirational goal, understanding style guides will help us all become better programmers. In particular, familiarize yourself with the sections under ‘Analyses’. We suggest re-reviewing the {tidyverse} style guide a few times per year just to be reminded of best practices.

Some general guidelines:

Use {tidyverse} functions over {base} functions, except in package development.

Use custom functions over for-loops.

If you use the same code chunk three or more times, make it a function and use

purrr::map()(or anymap()sibling).Use the {magrittr} pipe (%>%) over native pipe (|>).

Always include comprehensive documentation for your code.

4.1.1 Using the ‘Styler’ Addin

To facilitate adoption of the tidyverse style guide, please install the RStudio Addin ‘Styler’. To do this, click ‘Addins’ at the top of the RStudio window, then select ‘Set style’. This will prompt you to install the necessary packages and then define the style transformer. The default is {tidyverse}, so all you have to do is press ‘OK’. As you work on scripts within your repository, select ‘Style active file’. This will modify the file to conform to {tidyverse} style. Be sure to commit these changes. Styler will not tell you what has changed, all you will see is the following message in your console: While using {styler} will not correct all style choices, it will fix spacing, assignments, and tabs automatically.

4.1.2 Fonts, colors, and .css

[in development!]

In order to reduce any bandwidth necessary and get the most out of your coding deep work time, we suggest using a few hacks:

Use the style_snippets in this repo, which includes the ROSS colorway and ggplot themes for use in your code.

See the ROSS comms folder for pptx templates that include the colorways and fonts.

We use MONTSERRAT for headings and Roboto for main text in our documents. We are currently working on .css files and RMarkdown helps for easier integration of these into our workflow.

4.1.3 More on literate code…

One aspect of literate code relative to style is that we expect code and code

output to be readable in [nearly] any format. This means whether you are using

the Visual editor in RStudio, you’re reading a rendered .html or if you’re

viewing an .Rmd on the web or in the Source editor of R Studio. To accomplish

this, we suggest line character length no greater than 80. If you are in an

.Rmd file, just add the last code chunk from the

style_snippets/markdown_helpers.Rmd, save your file, and run the chunk. This

will reformat all lines of text so that they are on new lines every 80

characters. If you are in .R or a .md document, use the page-width indicator

(the light vertical blue-grey line on the right of your editor box) in the

Source editor in RStudio to determine when to create a new line in your text

block.

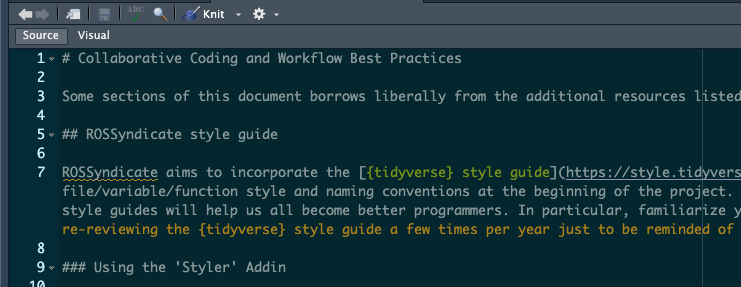

Here’s an example of run-on lines:

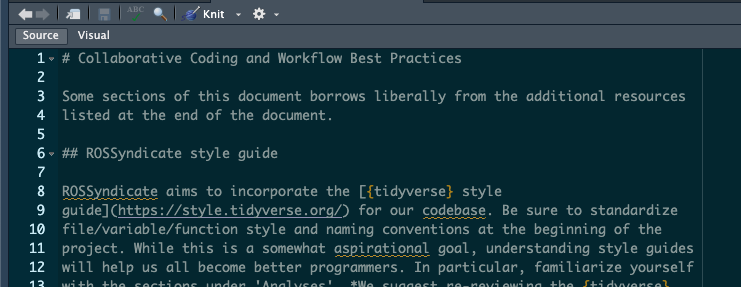

And what it should look like:

4.2 Commit history best practices

Always check your forked repository against the upstream repository before beginning your coding session and certainly before making any changes to the code base using the terminal command

git fetch upstream.Think about using your commit history as bullet-point summaries of your future pull request. If you need to go back and make some change in your commit history, you’ll want to have a good idea of where that happened.

Commits should apply to a singular file or multiple specifically-selected and related files. In general, this means avoid

git add .unless all the changed files are related - like a .Rmd and the rendered .html.Commits should briefly summarize the changes (e.g., ‘work on X’, NOT ‘end of day commit’).

Commits should describe WHAT and WHY you’ve made changes/added to your code.

Always commit your changes to your local repository or branch and push to GitHub at the end of your coding session as backup policy (i.e., don’t leave changes un-tracked when leaving work), ideally this also will result in a pull request to your internal creative partner. It’s always easier to write a pull request when your work is fresh in your mind.

4.3 Pull request best practices

The only time you should merge your own pull request is at the initiation of your repo, as described in ‘Create a New Project’.

Pull request should happen frequently, ideally at the end of each work session.

Pull requests should be 400 lines of code (LOC) or fewer.

Use the title of the pull request to help orient your creative partner.

Clearly identify what you need in the pull request review.

An example of a good pull request, that closes an issue created in your GitHub Project (we’re assuming issue #7 is ‘targets-ify the repo’), and makes a specific request of the reviewer:

Title: apply {targets} to workflow

Primary files for review are the _targets.R files in the main directory and in each subdirectory in the numbered directory step-by-step process. Please check for functionality by cloning and running

tar_visnetwork()for each _targets.R file.Closes #7

- If you have a large pull request, i.e. at the beginning of code development that is more than 400 LOC, write a useful description alongside your pull request that introduces the repo’s concepts (<awesome-workflow>) and highlights specific files (XXX, ZZZ) or commits (5e6b825):

Purpose: initialize development of YYY repo and start buildout of <awesome-workflow>

Start of YYY repository. Please review diff for XXX and ZZZ files. Otherwise, please do a high-level check of the repository as of the latest commit (5e6b825) for general workflow.

4.4 Pull request review best practices

Activate notifications for pull requests and comments so you know when a pull request has been submitted for your review.

If you cannot review the pull request that has been assigned to you before the end of the next work day, contact the person who has made the request via Teams to let them know when you *can* review the PR. The person who has made the review can then assign the PR to another person if the review is time sensitive.

If possible, cease work on this repo until the PR has been reviewed. Every additional

git push origin mainthat you make after you submit a PR and before it is reviewed and merged will be added into the current PR.If you MUST continue work on the repo while the PR is being reviewed, do so in a Feature Branch.

If the PR is not clear or does not contain specific asks, DO NOT REVIEW OR MERGE, message the pull request creator on Teams and request them to edit the detail of the PR to reflect the best practices outlined above.

“Before you even look at the code [for review], focus on understanding what was changed, why it was changed, and how it was changed.” – Leone Perdigão, Medium

Be kind and thoughtful with your comments. We encourage the use of ‘conventional comments’ labels found here. This allows you to clearly engage with the developer on the other end of the PR and offer actionable comments.

As a reviewer, you should not spend longer than one hour per session in active code review and never review more than 500 LOC per hour (SmartBear). Ideally, code review of a PR takes around 30-45 minutes when a project is in active development and follows the best practices outlined above.

What to look for in code review (via Google). Note that you do not need to check for all of these during a review of code as some are more applicable at the beginning of codebase development and others are more applicable to review that occurs closer to codebase deployment.

Design: Is the code well-designed and appropriate for your system?

Functionality: Does the code behave as the author likely intended? Is the way the code behaves good for its users?

Complexity: Could the code be made simpler? Would another developer be able to easily understand and use this code when they come across it in the future?

Tests: Does the code have correct and well-designed automated tests? We do not currently employ tests in our code. We will update information on this as we develop ways to include tests in our codebase.

Naming: Did the developer choose clear names for variables, classes, methods, etc.? Do they follow the tidyverse style guides?

Comments: Are the comments clear and useful?

Style: Does the code follow our style guides?

Documentation: Did the developer also update relevant documentation? This is especially applicable to the README.md files in your repository and directories.

4.5 Types of code review and engaging your internal creative partner

Code review is a skill that is learned and developed. Ideally, each member of the lab is performing some sort of code review on a weekly basis to grow skill in this realm.

[Some] types of code review:

Peer-to-peer code review

30-minute session explaining alpha-level code (code in baby development that might be in a branch or generally offline from the ROSSyndicate organization)

line-by-line code walkthrough meeting

30-minute to 1 hour ‘over-the-shoulder’ code observation and review

Code review via Pull Request:

‘process review’: This type of review is only suggested for early feature development OR early repository development. Do the decisions and workflow order make sense? Big-picture review only and/or suggestions to reduce processing time welcome. This type of review is either preceded or followed by a peer-to-peer code walkthrough and explanation.

‘general code review’: iCP reviews code changes according to usual pull request review best practices. This will be the most common form of code review via pull request

’ready for release: If a project features end-user reproducibility, i.e. Shiny app, published workflow, etc., the iCP should run this code in a fresh environment to make sure it runs properly and that dependencies are satisfied before pushing for public/partner use.

Ideally, code developers are engaging in some kind of code review on a daily to weekly basis

4.6 Additional Reading

The Best Way to Do a Code Review on GitHub, LinearB

GitHub Code Review Best Practices, Mergify

[How To] Commit and Code Review on GitHub, Birkhoff Tech Blog

Pull Request Best Practices, Medium

The (written) unwritten guide to pull requests, Atlassian

Best Practices for Code Review, SmartBear